“When I Am Among the Trees,” by Mary Oliver

It’s quite warm today, following a scorcher yesterday. Early June, and we’re in the 90s and I hate it. I don’t like the heat, and I want to do whatever I can to escape it. One option is of course to hide where there’s air conditioning. But I can also sit in the shade of a tree. Which I’m doing right now, and it’s delightful.

Delightful? Delicious? Spot where I’m sitting is under a junky Siberian elm in my back yard. It’s got four trunks, because I cut down one a couple of years ago when it was clearly leaning too close my neighbor’s house. What’s left of the elm spreads a nice canopy that so thoroughly shades this part of the yard that no grass grows here. Underfoot is just dirt and leaf litter and cones that have rolled over from the white fir that’s growing next to it. This whole corner of the yard is unkempt but shady and so for today the nicest place around.

I’m thinking about trees. So let’s look at Mary Oliver’s poem, “When I Am Among The Trees.”

When I am among the trees,

especially the willows and the honey locust,

equally the beech, the oaks and the pines,

they give off such hints of gladness.

I would almost say that they save me, and daily.

I am so distant from the hope of myself,

in which I have goodness, and discernment,

and never hurry through the world

but walk slowly, and bow often.

Around me the trees stir in their leaves

and call out, “Stay awhile.”

The light flows from their branches.

And they call again, “It’s simple,” they say,

“and you too have come

into the world to do this, to go easy, to be filled

with light, and to shine.”

I was prompted to think more about trees this week when I read about New Zealand’s announcement on Wednesday about their Tree of the Year. It’s a two-trunked beauty which, when viewed from the correct angle, looks like it’s walking. New Zealand, walking trees, Middle Earth: it all comes together.

I thought to myself about what I would choose as my personal tree of the year. And then I thought to myself that I don’t need to limit myself to a tree of the year. I can just choose a tree of the day. Every day, I can keep my eyes open for a favorite tree and bestow upon it the honor (quietly, just to myself) of being my Tree of the Day.

I could take a picture and keep track, and I like that idea. I could look back over time and see my favorites, remember what made them stand out to me. But I also like the idea of not photographing it at all. Like the line from the movie The Secret Life of Walter Mitty: “Sometimes when I like a moment, I don’t like to have the distraction of the camera. So I stay in it.” So maybe I won’t take the pictures after all, and just look—actually look—at the tree of the day.

Now let’s look at what Oliver actually does, poetically, in this text. Let’s see what makes it work.

In the first stanza, note how she makes her list of trees: “especially the willows and the honey locust, / equally the beech, the oaks and the pines.” What’s “equally” doing there? Why not just say “especially willows, honey locust, beech, oaks, and pines”? This is clearly an intentional phrasing on her part, and we as readers get to think about why. We get to think about “equally” and we get to think about why each one gets a definite article, “the.” The willows and the honey locust, etc. Pause for a moment and think about why she said it this way.

Really: pause and think. Don’t just move on to see what I say about it, I want you to think about it first.

If you are like most people (which you probably aren’t, but I imagine that you feel that you are), you have a thought about what it might could maybe mean. You don’t imagine that your thought is the correct answer, but you also didn’t just have a complete blankness. You didn’t think of nothing.

Based on my conversations with lots of people about poetry over the past couple of decades, I know that most people would have a thought and then immediately dismiss it. “It’s probably dumb,” they say to themselves. They think their thoughts about poems are poorly informed, are probably silly, or are likely to be wrong.

You likely come by your self-doubt honestly. You probably got it in school where you read poems and the teacher taught you that there is a right and a wrong interpretation. She taught that poems were like riddles that you needed to prize open to discover The One Correct interpretation. Even if she said otherwise, she actually taught the singular interpretation in example.

And while I’m confident that she was a lovely woman and that her cats adored her, she did you wrong. I understand why, because the sometimes-repeated sentiment that “a poem can mean anything; it’s up to the reader to decide” is also wrong. And that’s the way students want it to be, because that’s the easiest to BS. And where junior high or high school students start to BS, things spiral out of control quickly.

You, however, are not a high school kid trying to get away with something, having stayed up way too late playing Call of Duty and procrastinating a paper about Wallace Steven’s red wheel barrow. You are a thoughtful adult who isn’t worried about a grade here. You know that you’re free to just stop reading right now and walk away. And whatever you thought when you paused up above, it was good. I mean it: that thing you thought was smart and insightful. It was a good answer.

If you need to, take a minute and think about it again. Look at Oliver’s phrasing in those first three lines and why she did it that way.

Now, here’s what I thought. I thought that starting with “especially” implies that these are her favorites. And then, after listing off two, uses “equally” to give us the feel that the list of trees came about organically, in a single pure thought, stream-of-consciousness style. Her list of favorites starts out with just two, but then she remembers, all of the sudden, that she also loves many other kinds of trees. And it feels like she could add a few more on there. She’s playing a dual-layered game here, talking about specific trees, but also about all trees. The list feels infinite because she wants it to feel infinite.

I’m going to leave the second stanza to you, in part because this is getting long enough that you’ll stop reading, and in part because I want to jump ahead to my favorite bits.

I like the trees stirring in their leaves. Not the leaves stirring, but the trees are stirring in their leaves. What’s happening here? I think of my own poem that I shared yesterday about internal motion and stillness.

Later, light flows from the branches of the trees, and light fills the speaker. She is filled with light, and she shines (or, in other words, the light also flows from her). The light of the trees is something she sees with her eyes, something which fills inside of her, and something which also goes outward from her (to us?).

If you can, go look at a tree. Right now, if you’re inside move to a window and look at a tree. Maybe this is your Tree of the Day. It doesn’t need to be an objectively great tree, just a tree: roots, trunk, branches, leaves. Look at the tree: look at the bark on the trunk. Look at the shape of the leaves. Try, for a moment, to look only at the angle of some branches. Look at the leaves, and then look at the shade that the leaves provide. Look for a shade under a single leaf, and then look on the ground for the shade of all the leaves.

Can you see the light flowing out from the tree? Scientifically of course there is none. The tree is absorbing the light, obviously. But, even if you can’t quite explain it, you do know that Oliver is talking about—at least if you’re actually looking, really looking, at a tree.

You might enjoy listening to Oliver read this aloud herself:

While writing this, I’ve had to move my chair twice now as the sun moves and the shade shifts. It’s warmer now than when I started, even here in the shade of this Siberian elm, my Tree of the Day today. The breeze is starting to blow warm, but I’m not quite ready to pack it in yet.

I’m going to just stay a while. In the shade I’ll sit under this tree, my tree, today’s tree. It’s simple: I’m going to go easy, feel filled with light, and, I hope, shine.

A couple of related links that you might enjoy

Amy Stewart has an upcoming book about tree collectors. She did a little promo video about it here:

And of course there’s Overstory by Richard Powers which won the Pulitzer Prize for literature in 2019 and is a book I enjoyed very much, and the book that feels like part of Powers’s book come to life, Suzanne Simard’s Finding the Mother Tree (which I haven’t yet read but bought the audiobook).

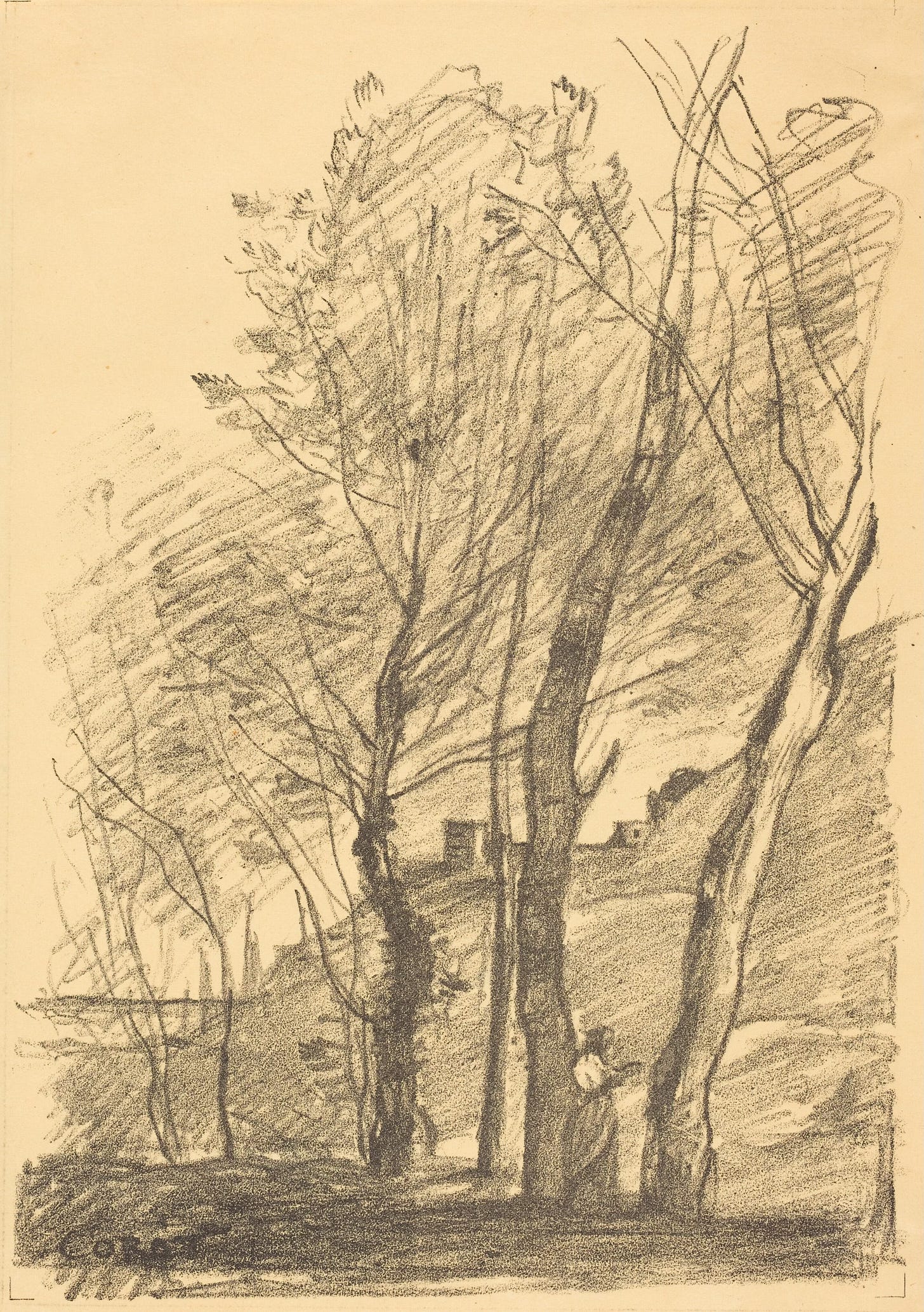

If you’re not looking closely at the artwork that I’ve included here, at least look at this last one, below. Look at the title: isn’t that perfect?