In the spirit of getting more prescriptive, this is the first of an intermittent and irregular series about how and why of poetry. Today: the portability of poetry, illustrated with a classic by Carl Sandburg, “Why Did the Children Put Beans in Their Ears?”

Text of poem

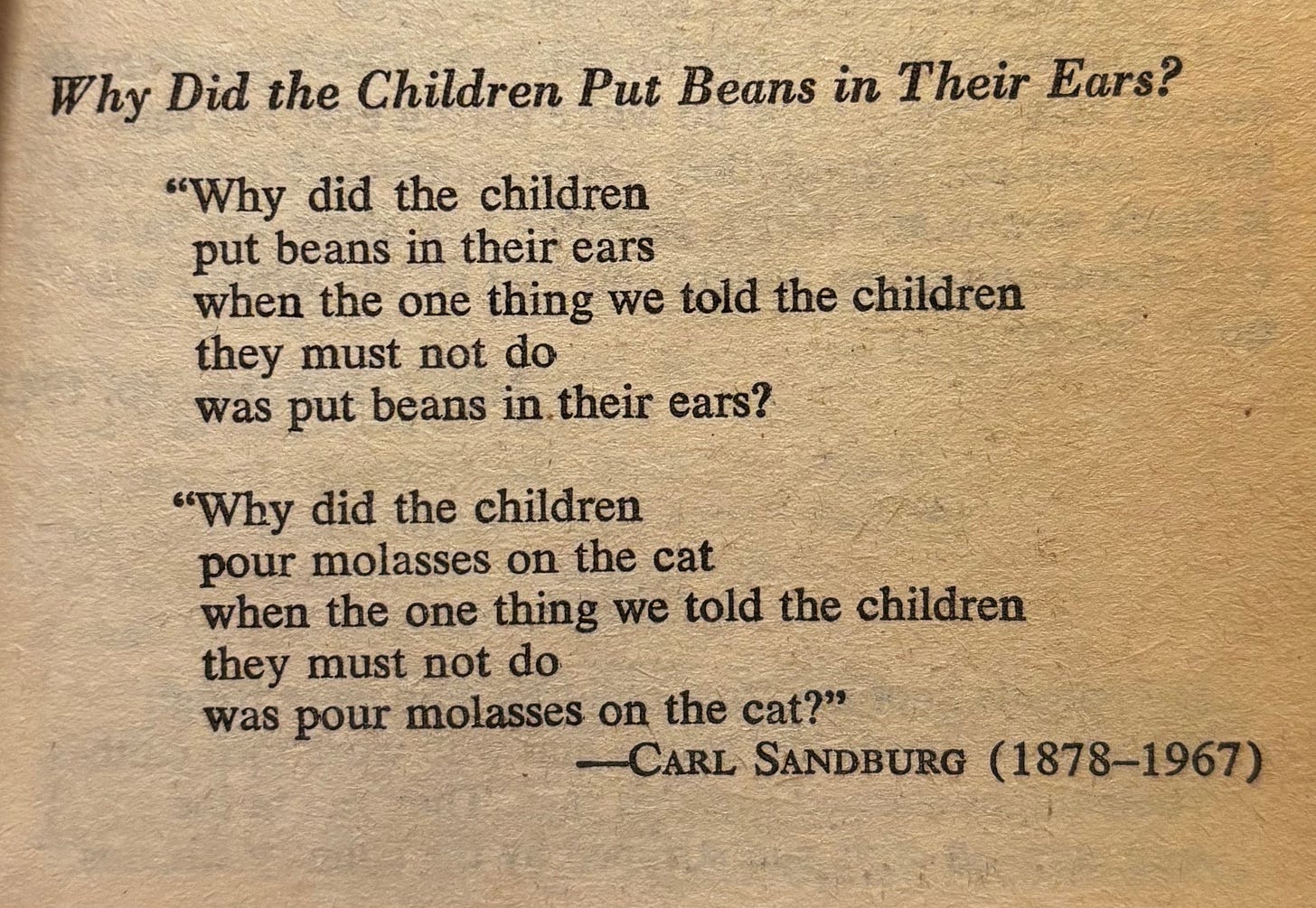

“Why Did the Children Put Beans in Their Ears?” by Carl Sandburg

"Why did the children put beans in their ears when the one thing we told the children they must not do was put beans in their ears? "Why did the children pour molasses on the cat when the one thing we told the children they must not do was pour molasses on the cat?"

I promised in the recording that you'd have it just about memorized by the time I was done with the episode. Let me know if that's true or not. I strongly suspect that it is, or close enough at least.

When I say that a poem is portable, I mean of course that you can carry it in your head. But here's an interesting thing that's true of poetry and very few other forms of art: what you have in your head is not a copy of the art, and it isn't a memory of the art. You have the thing itself. If you have the poem memorized, you have the poem, the original, all the time.

You may remember a song's performance, and you may remember a piece of visual art, but each of those are just copies. But for a poem, what is the original? While the manuscript in the poet’s hand is of course a discrete object on its own, the manuscript is not the poem. The poem is the words, and words are abstractions. When we write the poem down, we are simply capturing it. When you read it and especially when you memorize it, the action isn't happening on the page, but in your head.

And so, this Sandburg poem. I intentionally chose something easy to remember and apparently straightforward. But as I point out in the podcast, there are layers here. By memorizing this poem, you will discover times when it resonates with you, and the poem will grow in significance. You'll discover more meaning as you stick with it.

Share this post